Scripture Is Not a Weapon

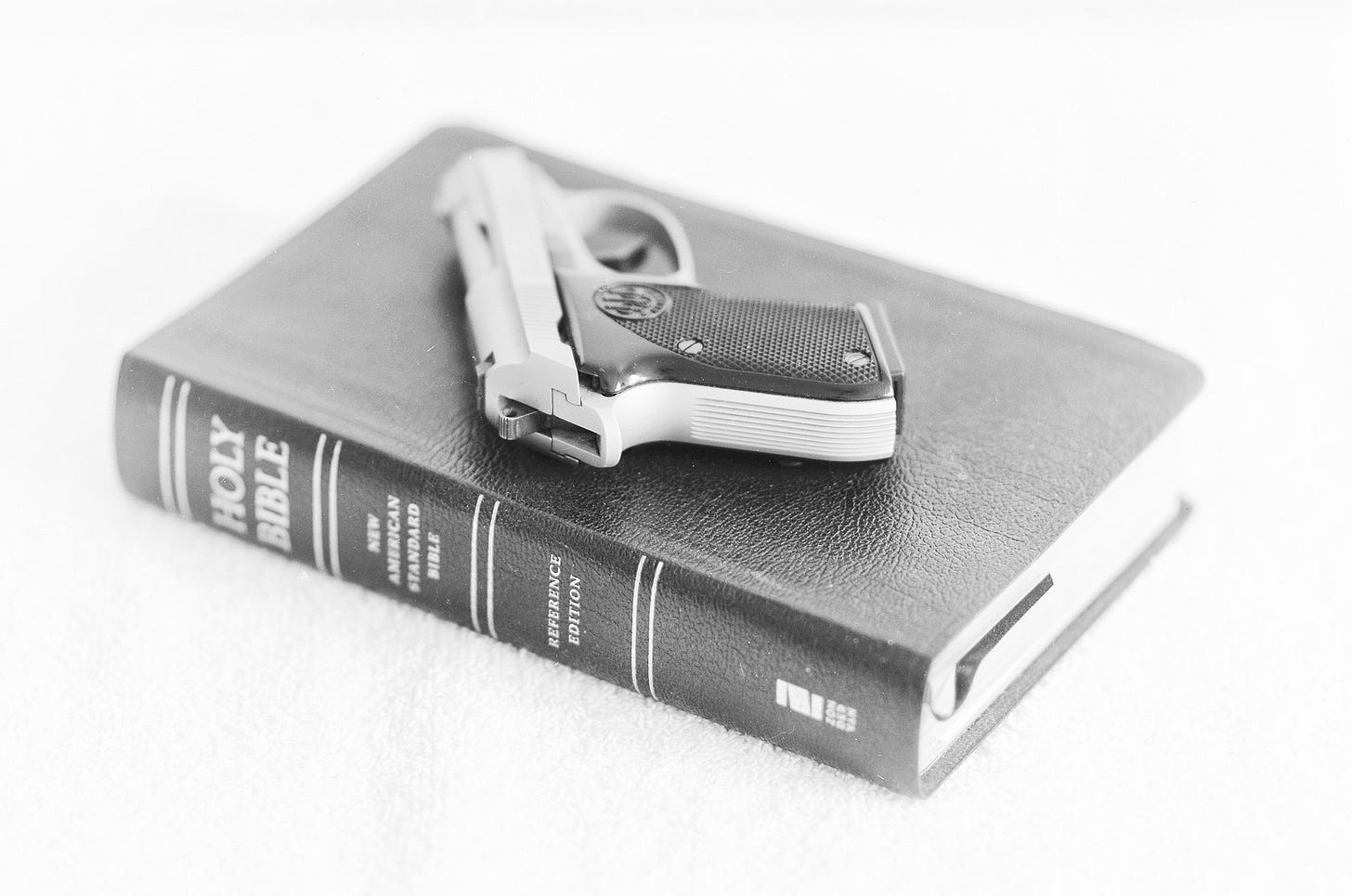

How one Bible verse has caused untold division and suffering, and what we can do about it.

I’ve spoken before of my fondness for the Eastern Orthodox teaching of theosis. Largely unknown in Western Christianity, this is a spiritual discipline whereby people figuratively graft themselves on to the person of Jesus, imitating him with the goal of becoming like God, or, in the words of 2 Peter 1:4, “partakers of the divine nature.” Theosis is, in essence, a spiritual union with God. It’s fair to say it might be the fullest and most meaningful expression of salvation within Christianity.

When Psalm 82 declares “I have said ‘You are gods,’” a verse that Jesus himself cites in the Gospel of John, theosis is what it’s pointing toward. Likewise, when Jesus tells us, in the Sermon on the Mount, to “be perfect, as your Father in heaven is perfect,” all he’s doing is expressing the ultimate goal of theosis. We “become by grace what God is by nature,” in the words of Church Father St. Athanasius.

Theosis is our spiritual birthright. In theological terms, it is the restoration to our original nature before the Fall. If we are, as scripture says, made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26) — and, moreover, if God is love (1 John 4:8) — then why on earth would we ever think of ourselves as filthy worms deserving of God’s wrath and punishment? God declared his creation good, not depraved, not evil. We are reflections of the divine. As such, we were always meant to be restored to our true nature. And according to Orthodox teaching, we can do just that, through Christ, with the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Why am I telling you this? Because theosis casts a very different light on a Bible verse that, tragically, has been the source of centuries of exclusivity, arrogance, self-righteous condemnation, even violence and bloodshed.

That verse is John 14:6.

What do you think when you hear Jesus proclaim, “I am the way, the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but through me”? Do you think it makes Jesus sound like some kind of divine gatekeeper? Do you think it means that Christianity is the only legitimate religion? That it has a monopoly on the truth? And if so, do you think that means it’s your job to convert people from other religions for the good of their own souls?

Many believers over the years have thought just that, resulting in conversions by force, persecution of so-called heretics, and countless other atrocities committed in the name of the Prince of Peace.

Let’s look more closely at that verse.

The Gospel of John is notable for the number of “I am” statements Jesus makes. Unlike the synoptic Gospels — Matthew, Mark, and Luke — John takes on a more mystical tone. Where the synoptics center on Jesus the man who leads his followers to God the Father, John places the emphasis on Jesus as God incarnate, right from its opening verse: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Likewise, the author of John later has Jesus flatly stating that “I and the Father are one.”

And so when Jesus employs a number of metaphors in this Gospel to refer to himself — “I am the door,” “I am the vine and you are the branches,” “I am the good shepherd,” and, indeed, “I am the way, the truth, and the life” — it’s not that the Jesus who taught the importance of humility in the Sermon on the Mount has suddenly become a raging egomaniac. It’s that the author has Jesus making a theological claim about himself that connects him to the scene in the Book of Exodus, when Moses asks God his name. God’s answer is generally translated as something like “I am that I am.” (More on this later.) In John, Jesus looks back to that moment when he proclaims, “Before Abraham was, I Am.”

So that means that in John 14:6, the verse that’s the focal point of our discussion, Jesus is saying that he’s God. Right?

Well, yes, but he’s also saying more than that. He’s saying “I’m God, and you are too.”

Wait, what?

Go back with me to the 10th Chapter of John, when Jesus quotes Psalm 82 to his Jewish opponents: “Is it not written in your law, ‘I have said, ‘You are gods’’?” His enemies are preparing to stone him for what they view as his blasphemous claim that “I and the Father are one.” Reminding them of the Psalm, he continues:

Why then do you accuse me of blasphemy because I said, “I am God’s Son”? Do not believe me unless I do the works of my Father. But if I do them, even though you do not believe me, believe the works, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father.

You see the distinction Jesus makes there? He’s telling his enemies not to accept his claim without evidence, but to see that doing God’s will is what substantiates his claim. Don’t believe the claim; believe the works. “Put aside what I say if you can’t believe my words,” he’s saying, “and instead watch what I do. Then you’ll see that I truly am who I say I am.”

This is why reducing Jesus to a ticket to heaven without actually following his example — which itself is an example of how to be like God — is a distorted and, frankly, illegitimate expression of Christianity. You have to walk the talk. Faith without works is dead (James 2:17). If no one comes to the Father but through Jesus, what that means is that you won’t find God until you strive to be like the one who claimed to be God. This is the heart of theosis.

Thus, John 14:6 isn’t about making a one-time mental assent to accepting Jesus as your lord and savior but then never transforming your own life. Nor is it about forcing others to make the same mental assent. It’s about picking up our own crosses and following him, refining ourselves through our own trials, persevering in the face of suffering and adversity, and meeting a broken world with love, even when that world mocks, ridicules, and persecutes you.

And what does that look like? How do you become like God? How do you come to the Father through Jesus? You love your enemies, turn the other cheek, go the extra mile, take the high road. You feed the hungry and shelter the homeless, knowing that what you do to “the least of these,” you do to Jesus himself (Matthew 25:40). You elevate love, compassion, and reconciliation over hatred, violence, and division. You “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8). That is what it means to be a Christian. And that is how you become a partaker in the divine nature. Jesus did it, and so can you.

What Jesus’ enemies didn’t understand is the same thing we misunderstand about him today. By saying that he and the Father were one, he wasn’t actually making some extraordinary claim to divine exclusivity. He was laying out a path, a Way, that was available to all who chose to follow.

Remarkably, his rather thick disciples didn’t seem to understand this either. Jesus tells them he has to leave them but reassures them that they already know the way to the place he’s going. Still, even after being with him for three full years, Thomas reveals how little he’s actually learned when he asks, and I’m paraphrasing, “How can we know the way? We actually don’t know where you’re going.” This is the context in which Jesus proclaims himself to be the way, the truth, and the life. “Just follow my example,” he’s saying. “Do the works that I’ve been doing. That is the Way. That is how you come to the Father.”

Then Philip chimes in: “Show us the way to the Father and that will be enough.”

At this point, you can almost see Jesus’ facepalm leaping out from the page. His response to Philip, only in nicer terms, is, essentially, “What do you think I’ve been showing you all this time, you knucklehead? I am in the Father, and the Father is in me. Don’t you get it?”

They didn’t get it, and there are a lot of knuckleheads out there today who run around saying “Lord, Lord” and still don’t get it.

Jesus must have felt like the Buddha, having experienced his moment of enlightenment but wondering if anyone would really understand what he was trying to tell them. What he wanted them to know is that he had unraveled the mystery of all mysteries. Like the Buddha, he had escaped from the wheel of samsara and set out to show everyone else how to do the same, in terms that he hoped his Jewish audience would understand.

Another way of stating it is that Jesus showed us how to tap in to our own Christ-consciousness. This consciousness, which is more or less synonymous with Buddha-nature, is all around us at all times, but as the Hindu mystic Paramahansa Yogananda stated it, “The little mind of the little man attached to little things” is too agitated and distracted to see it. This is the ordinary state of most humans, and it’s what the Buddha tried to liberate people from with his teaching of the Eightfold Path.

Christ-consciousness is, as Yogananda says, the universal cosmic consciousness manifesting in the material plane. To understand this from a Christian point of view, consider how Franciscan priest Richard Rohr draws a distinction between “Jesus” and “Christ.” The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke reveal the former, he points out, while John reveals the latter, the universal Christ of the spiritual realm, the Logos, which, according to Christian thought, has always existed. This higher, universal “Christ” took on flesh in Jesus. Through him, through the marriage of spirit and matter, of “Jesus” and “Christ,” we can discover our own true, higher nature, the Christ within us. In the words of St. Athanasius, God became Man so that man may become like God. We’re right back to theosis.

Let’s return for a moment to that scene in Exodus, where God reveals his name to Moses, for a deeper understanding of this point. In the Hebrew text, God’s reply to Moses is ehyeh asher ehyeh, which translates roughly to “I am that I am,” or, “My name is ‘I Am.’” You could argue that God basically said something like “I am ‘I Am,’” if you follow me here. The Greek equivalent used in the Septuagint, ego eimi ho on, means “I am the one who is,” or “I am being,” ego eimi meaning something approximate to “I exist.”

In other words, God is stating that he is synonymous with existence itself. There is nothing outside of the great “I Am.”

That’s what Jesus came to tell us: The kingdom of God is within us. There was never anywhere outside of oursleves to look. As the Hindus put it, tat tvam asi: You are that.

When we discover our own Christ-consciousness, all distinctions and divisions will melt away, and we see things for what they truly are. We discover that there’s no self and other, you and me, us and them, God and Man, but just an eternal, universal One. Christ shows us the way to that truth by being the Way and the Truth, leading by example, offering himself to us as a model to emulate. He’s a template, not a proxy. By “being” God, he shows us how to do the same.

Alan Watts, ever the one for a memorable insight, stated it this way:

Jesus Christ knew he was God. So wake up and find out eventually who you really are. In our culture, of course, they’ll say you’re crazy and you’re blasphemous, and they’ll either put you in jail or in a nut house (which is pretty much the same thing). However, if you wake up in India and tell your friends and relations, “My goodness, I’ve just discovered that I’m God,” they’ll laugh and say, “Oh, congratulations; at last you found out.”

This is, indeed, the true spirit of John 14:6.

I’ll let Fr. Richard Rohr have the final word on this often misunderstood verse:

Emphasizing perfect agreement on words and forms, instead of inviting people into an experience of the Formless Presence, has caused much of the violence of human history. Jesus gives us his risen presence as “the way, the truth, and the life.” No dogma will ever substitute for that.

Amen, Father.