Imbolc, St. Brigid, and Candlemas: Points of Convergence

At this halfway point between solstice and equinox, we look to a beloved goddess and saint to observe how the old pagan ways can harmoniously overlap with later Christian traditions.

The thing I admire most about the pagan ways of our ancestors is the way they connect us to the natural world and the rhythms and cycles of the seasons. Where some spiritual paths would have us renounce the material world and cast our eyes ever heavenward, paganism grounds us in the here and now, by reminding us that we are part of nature, not separate from it. Nor is it an object for us to consume, exploit, and dominate but rather a living organism that we need to live in harmony with. After all, if we screw up this world, where else are we going to go? More than that, why would you not want to treat your life-sustaining Mother Nature and Mother Earth with the love they deserve?

We don’t know a lot about the particulars of how pagan practices worked in various cultures. We just know that they were generally centered on devotion to nature-based deities to whom people made offerings in hopes for good weather, bountiful harvests, and success with fertility. Beyond that, much has been lost to history, either because traditions were handed down orally amongst cultures that no longer exist or because malevolent powers suppressed and destroyed what they didn’t want people to know about. As a result, much of what’s celebrated in pagan communities today is a result of stitching together bits and pieces of surviving lore (some of it of rather debatable authenticity), making best guesses, and synthesizing it all into a coherent reconstruction.

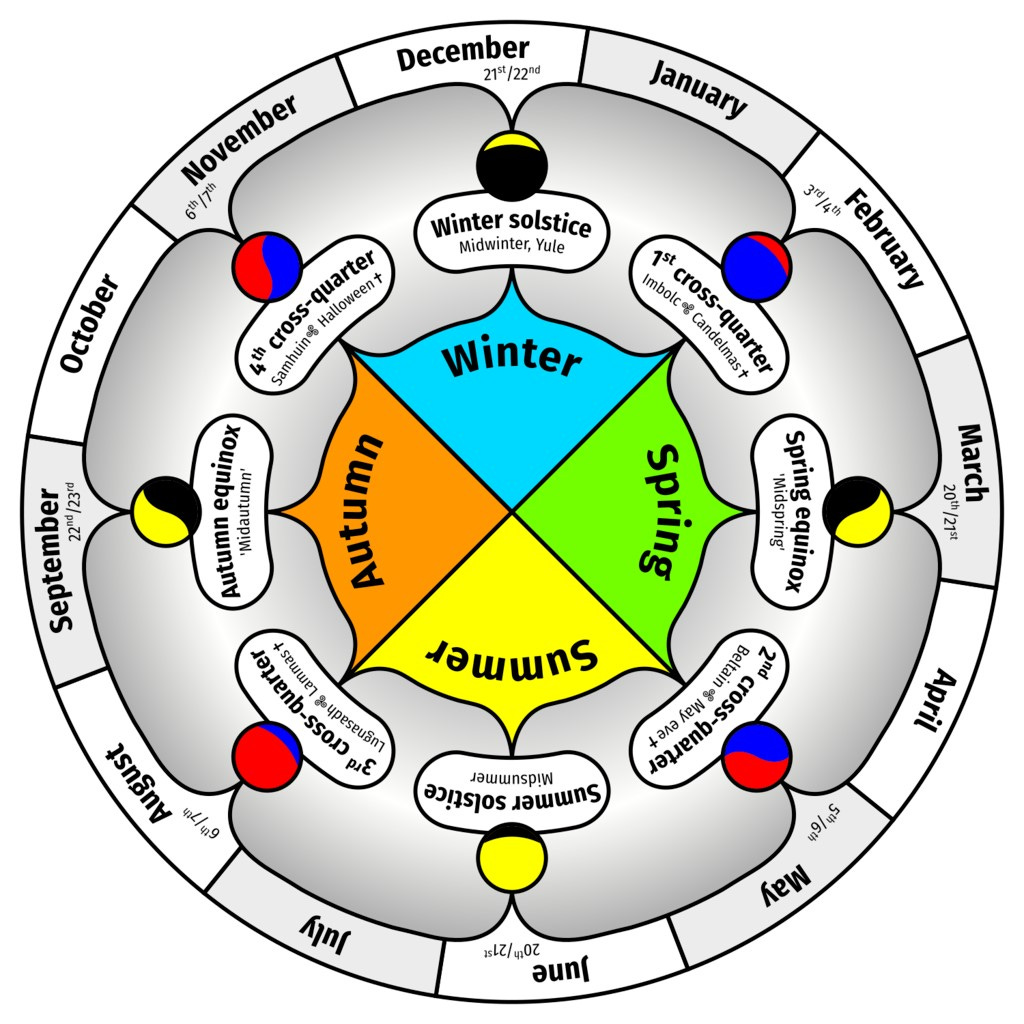

One of the things that emerged out of that process of mixing research with filling in the blanks is a concept that pagan communities call the Wheel of the Year. It’s a calendar of sorts that merges the observance of the solstices and equinoxes that was common to many ancient cultures with celebrations of the midpoints between those solar dates. For example, we know that Celtic society observed fire festivals at the halfway points, festivals known on the Wheel of the Year as Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain.

Coming up later this week will be the festival of Imbolc, marking the halfway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. We don’t know precisely when Imbolc or its other quarterly companion festivals would have originally been celebrated, but pagan reconstructionists have generally set Feb. 1 as the date for observing the day. There’s a reason for that, as we’ll later see.

It’s probably not a coincidence that the very next day, Feb. 2, is a historically significant date on the Christian calendar. It’s no secret, after all, that early Christians often deliberately situated their celebrations adjacent to pagan festivals, and even appropriated pagan rituals and imagery, in an attempt to convert the so-called heathens. See? the ancient missionaries would have said. You really aren’t giving up all that much if you join us. Our festivals even look like yours!

Then, of course, there’s Groundhog Day, which our family celebrates by watching the iconic Bill Murray-Andie MacDowell movie of the same name.

Let’s take a look at what all these celebrations have in common, and how we might be able to honor all of them, in the spirit of harmonizing without trivializing. That’s what we try to do here in the realm of Waymaking.

Candlemas, Presentation, Purification

The Christian celebration that falls on Feb. 2 has gone historically by many names. Today, the Catholic church calls it The Presentation of the Lord, or, more casually, the Feast of the Presentation. It marks the day when Mary and Joseph brought the infant Jesus to the temple 40 days after his birth, in accordance with Jewish custom. Women who had given birth were considered ritually unclean and were prohibited from attending the temple for 40 days after the birth of a boy, or 60 days for a girl. Upon the family’s offer of an animal sacrifice, the priest would pray over the new mother and restore her to full participation in the life of the temple. Moreover, firstborn sons were symbolically offered up to God and “purchased” back by the parents with a small monetary offering.

Until the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, this day was commonly known as the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. As one of its many ecumenical gestures, the council de-emphasized the Catholic church’s numerous Marian devotions, and accordingly, the name of the Feb. 2 celebration was changed to make it more Christ-centric. The church’s decision to distance itself from the human face of the Scared Feminine is something that hasn’t served it well, in my view, but that’s another sermon for another time.

In any case, the basis of the celebration comes from the Gospel of Luke, which documents the event in the life of the young Christ child. In the story, we’re told that the aged holy man Simeon blessed mother and son and prophesied that the child would be the savior of the world, while the prophetess Anna took the good news of the arrival of the savior to all who would listen.

Simeon also propheised that a sword would pierce Mary’s heart, in a foreshadowing of the crucifixion. Out of those words would grow the Catholic tradition that centers on Our Lady of Sorrows, an aspect of Mary as the compassionate mother who consoles us in our troubles and reminds us that we don’t suffer alone.

Finally, Simeon referred to the Christ child as “a light of revelation to the Gentiles,” and from that passage arose the celebration of Candlemas. Originally a day on which Mass would be celebrated with a candlelight procession, representing Christ as the light of the world, it later became a day when the church would bless the candles used in its services for the rest of the year. Eventually, it became a custom in many countries either to offer some of these blessed candles for churchgoers to take to their homes, or for parishioners to bring their candles to church to receive the priest’s blessing over them.

Candlemas, or the Purification of the Virgin, or the Presentation of the Lord — whatever you wish to call it — was traditionally the end of the Christmas season. Decorations would finally come down — in fact, it was considered inauspicious to leave them up after this day — and if your live tree had managed to survive this long, this was the day many families would take the remains outside and burn it, in a final farewell to the season.

It’s cold out there today. It’s cold out there every day!

You wouldn’t think Punxsutawney Phil would have anything to do with religious observances. But as it turns out, Groundhog Day appears to have its origins in a folk belief among German immigrants to North America that if a badger saw its shadow on Candlemas, we could expect another six weeks of winter. (We’d get another six weeks of winter either way, of course, but even the goofiest of traditions are fun, aren’t they?) In the Pennsylvania Dutch dialect, “badger” became “groundhog,” and a tradition was born.

The badger/groundhog lore, in turn, appears to have developed from older traditions that simply stated that a sunny Candlemas meant more cold weather ahead. We also know that snakes and birds served a similar function of weather prediction in Scotland and the Isle of Man, respectively. But in those places, the day for the prediction was not Feb. 2, but one day earlier.

To understand why, we have to take a trip back to pagan Ireland.

The two faces of Brigid

2023 will mark the first official celebration of St. Brigid’s Day in Ireland as a national holiday. Traditionally, the day has been marked by parades, festivals, hisotrical talks, music, and pilgrimages to sites associated with St. Brigid of Kildare.

“But wait,” I hear you saying. “You just said Saint Brigid. That signifies a Catholic saint. Where does the pagan connection fit in?”

The clue is in the name that the saint shares with the earlier Celtic goddess.

Brigid the saint, according to the lore, was the founding abbess of a monastery at Kildare, where she and her nuns kept an eternal flame burning, again symbolic of the light of Christ. Little is known of her life, and most of the stories that come down to us are fantastical tales of miraculous events attributed to her holiness. For example, one legend holds that she was transported back in time to the first Christmas, where she became the wet nurse of the newborn Jesus.

It’s also said that the bishop who ordained her as an abbess was so overcome by her holiness that he “accidentally” consecrated her as a fellow bishop! That is perhaps why the saint is often depicted in art holding a shepherd’s crook, a symbol of a Catholic bishop. Were the Irish people making a pointed commentary about the Catholic prohibition on women in the priesthood? It can certainly be interpreted that way.

The bottom line is that Brigid the saint just happens to possess numerous qualities that had previously been associated with the Celtic goddess of the same name. It’s possible that there was a Catholic abbess named Brigid whose biography was embellished over time to make her overlap with the pagan deity, or it could be that when the Christians came to Ireland, they found that the natives were unwilling to part with their beloved goddess — and thus was a legend born, so to speak, to bridge the gap (no pun intended) between the pagan and Christian worlds.

To the best of our knowledge, the goddess Brigid was honored on Imbolc with — among other things — bonfires, symbolic of her status as a deity of illuminating fire, and corn cakes, in thanks for her protection through the winter months and as an offering for an abundant growing season to come. As she was associated with dairy animals, some people would leave a cup of milk out for her or would spill a cup on the ground as a libation. Relatedly, the original meaning of the word Imbolc appears to have been “in the belly,” which would have referred to the ewes who became pregnant around this time of year and therefore could begin to be milked at a time when farmers’ winter stores might be running low. Farmers probably focused on getting their sheep to reproduce before their cows because the sheep could more easily survive on what little vegetation was available in what was still a cold time of year.

The lives of Brigid the saint and Brigid the goddess are so tightly intertwined that it’s often hard to tell where one begins and the other ends. Both are associated with cows and dairy (the saint was said to have taken sustenance from a red-eared white cow when she was a poor slave girl), with poetry and wisdom, with fire, and, paradoxically, with holy wells, whose water is said to bring blessings and healing powers. The tradition of tying clooties, strips of cloth, to trees near the wells began in the pagan days and carried over to Catholic Ireland. And while the tradition of weaving Brigid’s crosses is associated with the saint, it’s likely that the symbol itself dates back to the pagan sunwheel.

But what does any of this have to do with weather divination? Well, Feb. 1 was traditionally believed to be the day when the Cailleach, a hag in Celtic legend who controls the cold winter months, would emerge to gather firewood for the rest of the season. If the day was sunny, that meant the Cailleach was creating ideal conditions for her to go out and collect plenty of wood, which meant she was preparing for more cold weather ahead. A day of bad weather therefore meant she was asleep and winter was nearing its end.

The Cailleach legend is undoubtedly the origin of later animal-related weather divination traditions, like Groundhog Day — which came to be associated with Candlemas in the Christian era. It likewise made sense that Imbolc would have been celebrated around this same time, given the day’s importance in marking a turning point of the winter, when the days would get longer and warmer and farmers could begin preparing for the new growing season ahead.

And so, with just a little bit of imagination, you can begin to see how you might be able to tie all the different celebrations together.

You have the goddess of fire, the saint associated with the perpetual flame, and Simeon’s prophecy of light as symbolized in the darkness-dispelling candles of Candlemas.

You have the goddess Brigid, the saint with goddess-like powers who’s known as the “Mary of the Gaels,” and the day of the ritual purification of the Virgin Mary.

You have the pagan observation of the turning of the seasons and the coming renewal of abundant life, the saint who was said to have nourished the infant Jesus with her life-sustaining milk, and the birth of the one who, according to Christian theology, would defeat death and open the door to eternal life.

And so on.

You’ll find plenty of times throughout the year when pagan and Christian celebrations converge like this. Christmas and Yule always occur within days of each other, for example; and Samhain, the night when the veil between the living and the dead is at its thinnest, is followed by All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. Secularized, the old pagan tradition carries on as Halloween, while Catholic and folk traditions have merged into Dia de los Muertos in Mexico, with its ofrendas for departed loved ones and its decorative sugar skulls. But rarely will you find Christianity and paganism so tightly intertwined as on Imbolc, where the person of Brigid takes on characteristics of both traditions simultaneously and in complete harmony with each other.

The peaceful blending of the Brigids is a model for what I envision for Waymaking, a spiritual approach that seeks to discover and promote commonalities among different religious and spiritual paths without trivializing any of them. If you don’t feel the need to take a side between Brigid’s Christian and pagan faces, you can find plenty of ways to celebrate the day — Feb. 1 or 2, or both, if you like — that touch on both aspects.

Armenian tradition is for farmers to spread ashes in their fields to bring about a good harvest. You could perhaps do the same on the site of your springtime garden plot.

Many pagan celebrations involve jumping over a fire, symbolic of the transition from life to death we all must make, of spiritual cleansing and renewal, or in some cases of the need for newlywed women to purify themselves before becoming pregnant.

In some Catholic and Orthodox cultures, a candlelight precession would be held the night before the feast day, emblematic of piercing the darkness with the illuminating light of Christ. The candles would then be taken home to light lamps or to start bonfires.

Modern pagans sometimes mark the day with some spring cleaning. Depending on where you live, it may still be cold and snowy at the beginning of February, so not everyone may feel inspired to take this step just yet.

Make some crêpes. It’s tradition in France and Belgium to mark the day with the golden discs, representative of the return of the sun and warmer days ahead.

Drink a glass of milk, pour one out as a libation, or leave one outside for Brigid as she makes her rounds on the eve before Imbolc. You could also leave out a beer for St. Brigid, who was said to have possessed the abilty to turn water into beer. Forget the wine — St. Brigid knows how to celebrate like a proper Irishwoman!

Leave out a piece of clothing for Brigid to bless. Like a female Santa, Brigid leaves blessings as she travels the world — offering spiritual instead of material gifts.

Tie your own clooties to a tree. Traditionally, the idea was to attach a prayer to the clootie, and as the fabric rotted on the tree, so would your troubles. For that reason, it’s advisable to use a natural and biodegradable fabric like cotton, as opposed to a synthetic like polyester. You don’t want your troubles to linger on that tree forever!

Make a bed for Brigid so she can rest on her journey, in honor of an old Irish tradition. Some families would smooth out the ashes of their fire before bed and see if they could spot any footprints from a spiritual visitor in the morning.

Mark the day by starting a perpetual flame, in honor of the goddess of fire and of St. Brigid’s monastery flame. Take precautions if you plan to do it in your home, of course. Alternatively, see if there’s a way you can keep an eternal flame going outdoors, perhaps using an oil lantern on a hook.

Find a creative way to honor other fire deities, such as Hestia, the Greek goddess of the hearth. Or take a moment to give thanks to Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods to share it with humanity.

Make a doll of rushes, wheat, or corn husks. Traditionally, children would take their creations door to door asking for treats for the doll, either in the form of candy or adornments, in a kind of trick-or-treat ceremony. Often, the doll would be kept by the hearth for the rest of the year and then burned before a new one was made.

Donate to a charitable cause. In addition to carrying their dolls to neighboring homes, some children would ask for pennies for Brigid, which would then be donated to the poor.

Attend a religious ceremony. The Catholic church has Masses year-round, so you could attend both on St. Brigid’s Day and on the Feast of the Presentation/Candlemas if you wished to.

Watch Groundhog Day. Despite its lighthearted silliness, the film invites us to ponder some deep spiritual questions: How does karma work in the context of how we treat others? Do we really have to keep coming back to this world, one lifetime after another, until we get things right? Will transcending the ego and loving others liberate us from our own suffering?

And, of course, make a Brigid’s cross. Perhaps no other symbol better embodies both the goddess and the saint. Legend holds that St. Brigid weaved a cross from straws on the floor of a pagan chieftain’s home as the man lay dying. Intrigued by her actions, he converted to Christianity on his deathbed. It’s likely, however, that the Brigid’s cross has its origins, as mentioned, in the pagan sunwheel, which was probably hung in homes as a ward against fire and evil in pre-Christian Ireland. Like the Brigid dolls, the crosses would be burned after a year and a new one would be woven, beginning the cycle anew.

Inspired by the arms of the Brigid’s cross that point out in all four directions, may we reach out beyond our own cherished traditions to embrace commonalities in other paths, as we celebrate this turning of the Wheel of the Year in the spirit of charity, cooperation, and goodwill. Happy Convergence Day!